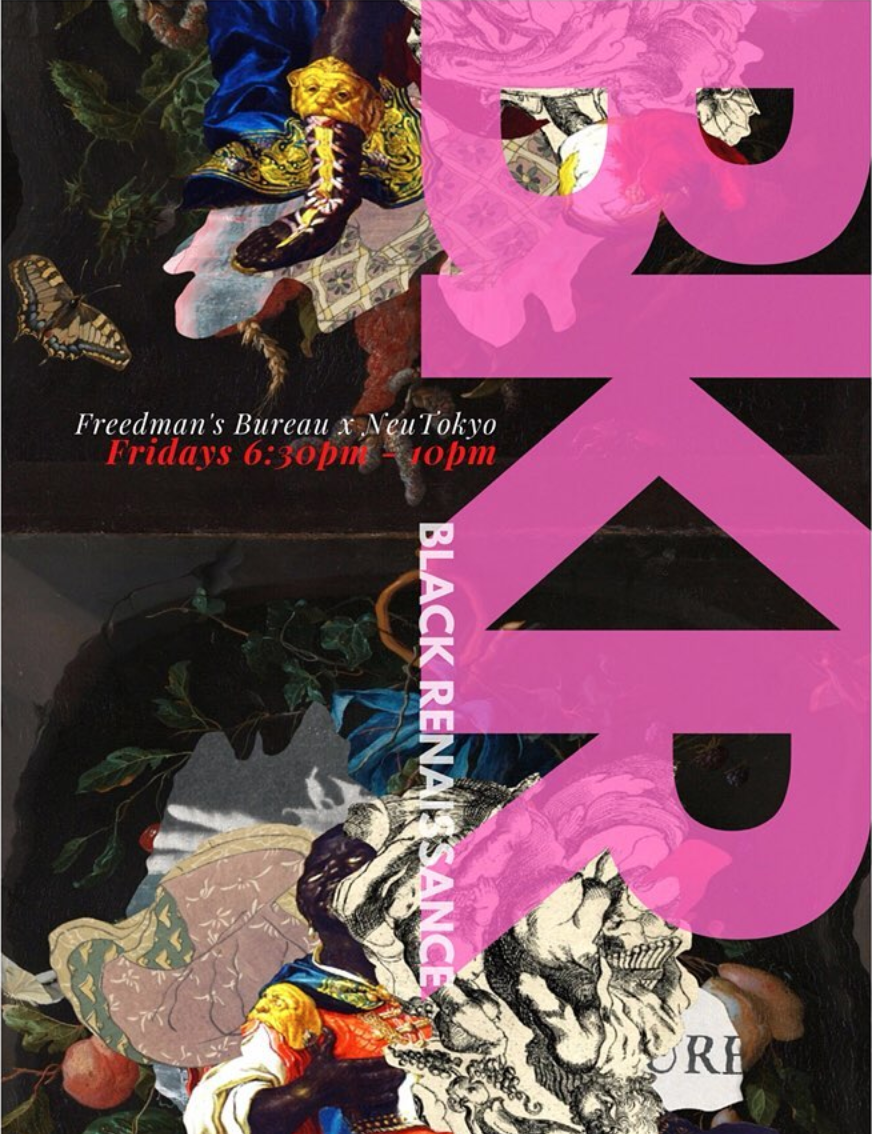

Aaron Marin Celebrates Black Identity & the Human Connection

Aaron Marin (he/him) is a New York-based collage artist and illustrator on a mission to erect a space for Black artists in Tokyo, dismantle capitalism in the art industry, and decenter white faces and voices in art and fashion.

Aaron Marin

Freedman’s Bureau x Neu Tokyo poster, 2020

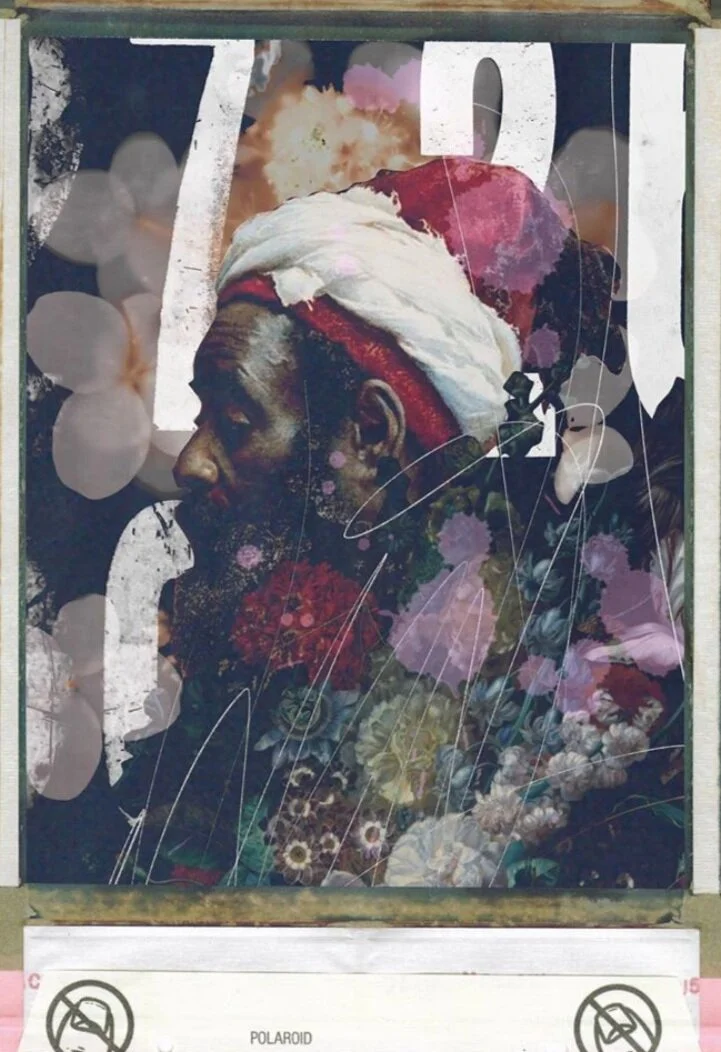

Aaron Marin

Untitled (Polaroid of Moor), 2020

Victoria: Tell me about your artistic process.

Aaron: It’s varied throughout the years—most of the time I simply just want to make art. My recent work, “The Black Renaissance,” centers Black figures I’ve found in early European art, which were almost always in the peripheral of these massive oil paintings. It was spurred by interviews by Kerry James Marshall; he’s famous for solely painting Black figures in the Rococo style. My methods vary [based on] what I can afford to create. Although some of my work is analog, I’ve been increasingly creating digital work. The scarcity of physical resources (i.e., few images of Black figures) in both modern and vintage magazines has forced me to find what I need online. I live in Upstate New York, so access to vintage Black magazines and paper ephemera is extremely rare. With modern magazines—well, I think you can count how many people of color (let alone black women) are in one magazine on [on one hand]. It’s never a lot, and like the old European oil paintings, the Black subject is always marginalized and in the periphery, never getting the main stage unless they are an exceedingly famous actor, musician, or model.

V: You bring up a good point. Other artists (such as Mickalene Thomas, Romare Bearden, April Bey, etc.) use(d) collaging as a catalyst for this conversation surrounding racial and economic disparity, gender issues, and identity. How do you fit into that?

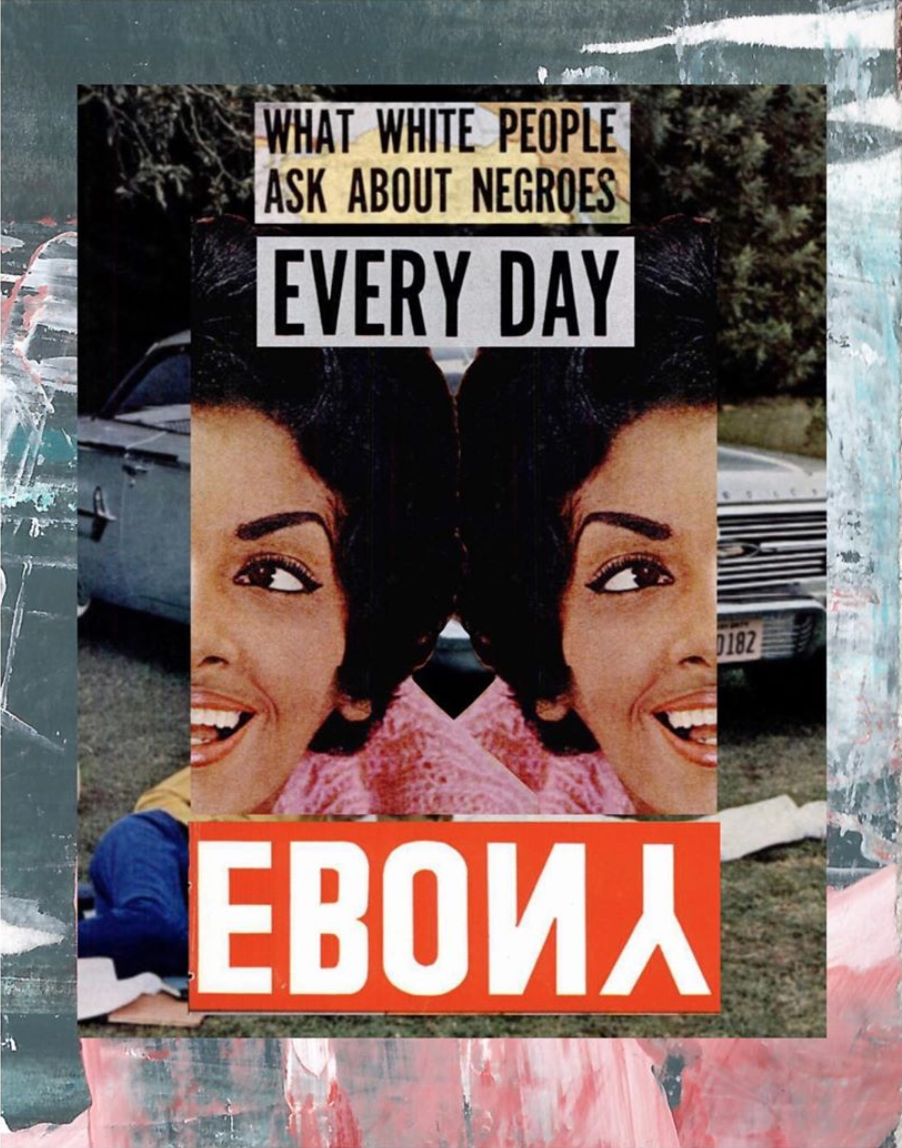

A: My more recent works are most definitely focused on African American identity. That came about because I kept seeing [few] Black faces throughout modern fashion magazines. It should be no surprise because we don’t own the fashion houses that market [in these publications] or any of the magazines themselves. (We aren’t even art directors of the magazines, so of course the images are white.) I was getting sick and tired of seeing that. I was getting sick and tired of reading stories of white women and their “struggles and triumphs.” With every page turned, it was like programming and indoctrination. I didn’t want to keep giving voice to that, so I stopped.

My work isn’t always as well thought out as the artists you mentioned—perhaps it’s because I’m so anxious to get my work out there. I just want to flood Instagram with images of blackness, abstract blackness, concrete blackness, Dadaism blackness. I honestly don’t care as long as the image is Black and uplifting in some way because I know that there just isn’t enough Black art, period. I don’t care what anyone says about how many prominent artists we have alive (or dead); it isn’t enough compared to what is getting out there—what people are seeing isn’t enough.

V: You bring together analog and digital techniques to create a hybridized work that I’m utterly obsessed with. Tell me why you use both?

A: It’s an experiment born out of a need (and desire) to make images within the smallest space possible with the least amount of resources. I use an iPad, a scanner, and my laptop together with some magazines and a cutting tool. I used to only want vintage paper—mostly because I was copying other artists and partly because I loved the old typography and faded colors in [old] magazines. But it wasn’t practical. I don’t have a studio, and I was making a lot of work in a coffee shop or at my dining room table.

V: Oh, so do you prefer to work at home or elsewhere?

A: I love making work outside of my home—it’s a way [to interact] with people without having to talk to them—but since it’s not my house, I can’t bring all these magazines, glue sticks, and cutting stuff. When I wasn’t doing digital, I would challenge myself to bring one magazine (maybe two) and make images only with limited resources. Digital opens my options while also staying minimalist in my gear. I can scan a whole bunch of stuff at home, email it to myself or save it on my Google Drive, then just bring my iPad and work anywhere. I will say that [digital] doesn’t have the same feel for me, but it does allow some freedom to play around and make non-destructive artistic choices using the same materials. It’s nice, especially when your materials are often out of print like vintage Ebony, Life, Look, or Esquire magazines.

Aaron Marin

Every Day!, 2020

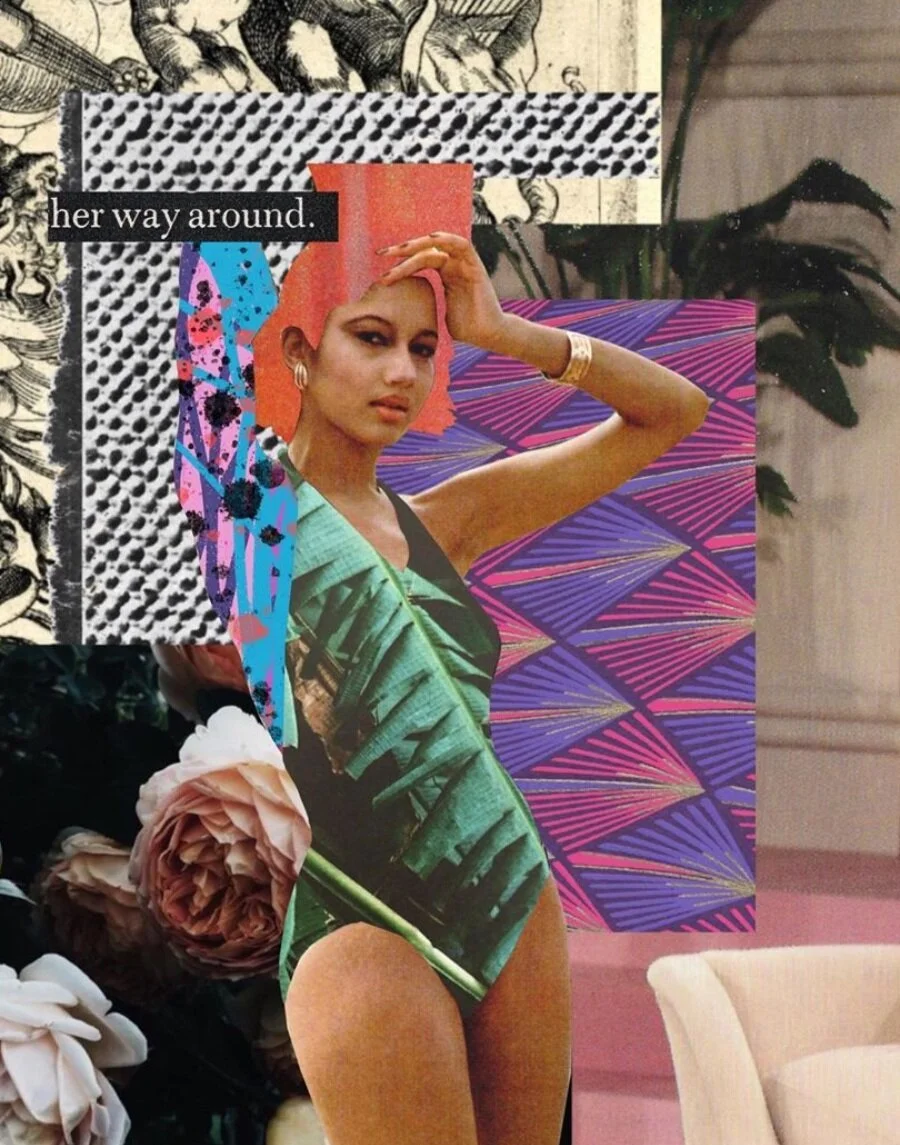

Aaron Marin

Her Way Around, 2020

V: Right, so you end up using mostly fashion and lifestyle magazines. Fashion and adornment make up a unifying theme within your work. Is there an inspiration behind this, and do the genders of your subjects play a role?

A: Fashion and adornment are a product of the materials that I choose to use at the time as opposed to a conscious artistic choice. I used to photograph, mainly portraiture of women. Women have been central in my life, or rather prominent figures. Women’s fashion is unique, and magazine photography is always inspiring. Men’s fashion is pretty bland, for the most part. It’s not inspirational, and very little chances are taken in displaying the male figure in anything but stereotypical machismo.

V: So, what is the inspiration or aim?

A: My goal with my work is for people to see the nuances of blackness. I went to private schools and my parents are both physicians who graduated from Yale. I grew up listening to rock & roll, ‘80s synth bands, EMO music, hip hop, folk music, Paul Simon, Ladysmith Black Mambazo—my taste was all over the place. I like comic books, cartoons, fashion magazines, and weird cooking shows. I'm all over the place. It took me a long time to find other Black people like myself—not solely in terms of my upbringing but also my eclectic taste. That doesn’t mean they didn’t exist, but our access was limited. I was often one of one at jobs that I held and schools I [attended], so it’s important for me to show that my art displays another layer of blackness to the world, and more importantly to other Blacks.

V: Do you have any unusual techniques you employ to make your work unique?

A: Not really. I think a lot of my work looks like portraits to me. I don’t create landscapes or scenes with multiple characters like Romare Bearden did—not that I don’t want to; its just something I don’t work on. I still like photography, Andy Warhol’s screenprint portraits, and pop art graphics because those images and styles are seared into your mind. They’re quick, impactful (whether you love or hate them), and there are myriad messages sometimes.

V: I love that you don’t simply post your work to Instagram & let the images collect ‘likes’. You offer a glimpse into your techniques, moods, & inspiration/concepts in almost every most caption. Why is this kind of transparency important for you?

A: Okay, so I could talk about this forever. Sometimes, I’m more interested in how someone did something than the actual finished piece. I’m also interested in why someone did something, or maybe their thoughts on creating. For me, there isn’t a desire to know what the artist thinks their artwork should mean—that doesn’t interest me at all. I think a lot of this desire for understanding comes from my time working in military intelligence. We focused on the 5 W’s: who, what, when, where, and why. The most [important] was always “why” because unless you ask your adversary or they write it down, you will never know. All the other W’s can be ascertained.

I like giving [the why] away. If people ask, I tell them. Why not? I used to ask other Instagram collage artists about their techniques, and they would never respond. I could see they read my DM and just flat-out ignored it. That would piss me off because that meant to me that they were hiding behind [their] technique. Not that an answer is owed to anyone, but I saw it as if they were trying to hide a trade secret. It’s nonsense because nothing they were doing was truly original, and even if I copied them, I could never duplicate what they were doing just by the virtue of me being me. Anyhoo, I give away a lot. The inspiration doesn’t come from me; these ideas I put into my art are not unique, and they’ve been [applied] before, so why not share? [This way I] create dialog, then I [get to] meet other people. They share ideas, opportunities—the results are endless. I love meeting people. Despite its inherent toxicity, Instagram is also a great tool for that if used correctly.

Plus, ‘likes’ are stupid. There’s no denying that they feel good, but they’re not putting money in your pocket or creating dialogue. (It’s temporary self-gratification that feeds that narcissistic voice in your head.)

V: I can appreciate that you having a loose relationship with social media in the sense that you don’t let the race to notoriety or a large following drive your desire to share your work. How else do you maintain your terms of engagement in this sphere that many artists and other industry players have become so dependent on then?

A: Instagram is a tool, one of many. I know I’ll never be able to do the things that a lot of other people do to garner their massive followings. I simply don’t give a shit. Do I want more followers? Sure. Followers allow, hopefully, more people to see my art and maybe garner more opportunities. I would delete Instagram in a heartbeat and never use it or any other social media [platform] again if someone were to offer me a studio, a modest income, and the ability to work with other artists (by hosting their work, talks, or group classes). Social media is an echo chamber; it’s not real.

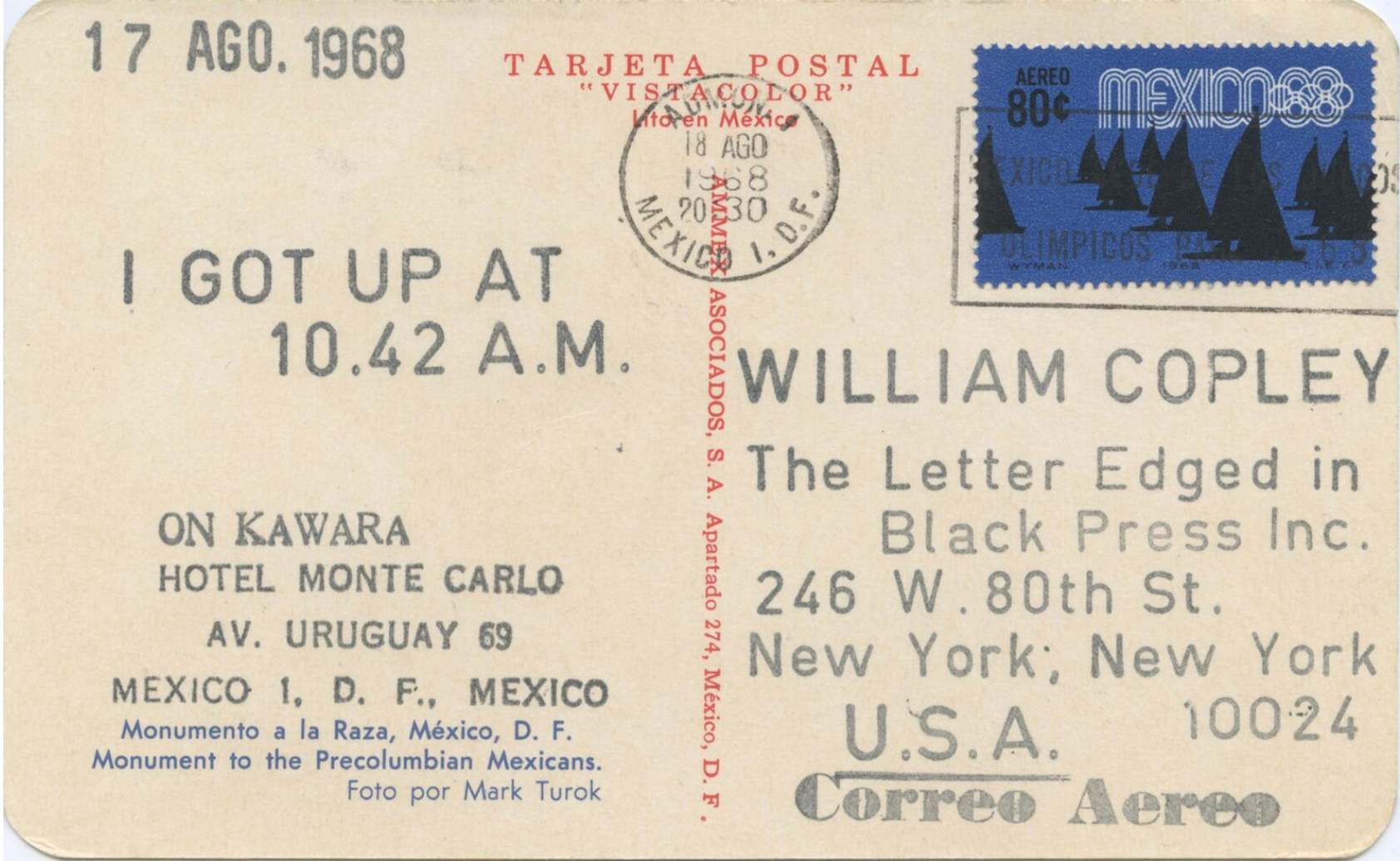

I started and have done so on more than one occasion (pre-Instagram) sending postcards with my art. This isn’t a new idea—tons of other artists more famous than I have done this. The most influential to me was the work of Japanese artist On Kawara. He created a series of work called “I GOT UP” between 1968 and 1979 in which he sent two different friends or colleagues a picture postcard every day. [Each postcard] was stamped with the exact time he arose that day and the addresses of both the sender and recipient. I love that. That’s real! That is taking the time out of your day to think of something and someone, create, then send it out into the world.

On Kawara

From the series I Got Up, 1968-79

On Kawara

From the series I Got Up, 1968-79

V: Yeah, you seem to be all about fostering a community through your work: you allow anyone to contribute to zines you’re working on or offer to trade materials instead of a monetary payment.

A: Yes, I’m very sensitive to people’s current economic situations! The economy is shit right now—from COVD-19 and increased job competition to trying to find work that isn’t hourly. It’s tough out there, and for me as well. I’ve been scrimping and saving—it’s been tough to find stable work for the last 8 years. I did all the things I was supposed to do: [academic] degree, military career, retrained in another profession. It’s been a constant struggle to find stability. I 100% get it and hence the trade idea.

However, I’ve had only one person take me up on an offer to trade my artwork for their artwork or something in kind. I think people have an aversion to finding something of value outside of the construct of cash. I understand it: We have been trained to equate money with value. But it’s sad to me because money is easy and also empty. The harder thing is to find something of value to trade because you have to ask the hard question, “What do I value?” It’s a lot to ask of people who simply like your art and want to have it in their life.

V: Do you have an interest in building a collective?

A: Yes, I do! The goal for me at the end of the day is to create an artist residency/café/gallery in Tokyo. There’s an older part of the city that is filled with artisan workshops, quiet streets, and a ton of cafés. I love it! The idea of the space is to only focus on showcasing BIPOC art with a primary focus on African diaspora art. The café aspect of it is because I love coffee, I love good café space. I love that they can be a meeting space for different thoughts. I’ve had this idea for at least a decade. I went to cooking school and worked briefly as a chef and a bartender just to see the underbelly of the service industry.

V: I found solace writing in coffee shops pre-quarantine, too. You can get away to clear your mind without spending too much or trekking too far from home.

A: My first collages were all done when I was trying to escape the world, my thoughts, my broken heart. I found quiet refuge in coffee shops. The sound of the espresso machines, the din of conversation, music in the background, the clanging of dishes—all of that was the soundtrack to creating my work. But even before then, I loved cafes. The ones in Lisbon where businessmen came in the morning for a pastry and espresso before dashing off to work, where retirees and artists sat outside and read the newspaper and savored their drinks—so romantic to me.

V: The idea of an art residency, café, and gallery all rolled into one is very romantic. Have you applied to a residency before?

A: I’ve applied to numerous residency programs and have been denied by every single one of them. I realized they mirrored the art world—very white and incestuous. They were only looking for “established” artists who could bring prominence to their space. It wasn’t a meeting of the minds as opposed to another racket within the art world, which is giving people who can afford to travel and make art (most residencies are very expensive) more space to do that. It’s a self-licking ice cream cone; I don’t want that. I understand that travel and art are expensive, but I want to attract people who can’t afford to do either. I think having grants, crowd-funding, and maybe some type of scholarship program would offset some costs for artists.

The travel that I was able to do while in the Navy impacted me tremendously. It was one thing to read about a country in a textbook or see it on the news, but to be there and live it? That’s real; that experience is genuine. And when you come back home and people try to tell you what the world is like, you know you have lived some of it. Your perspective changes how you see yourself, and that’s important.

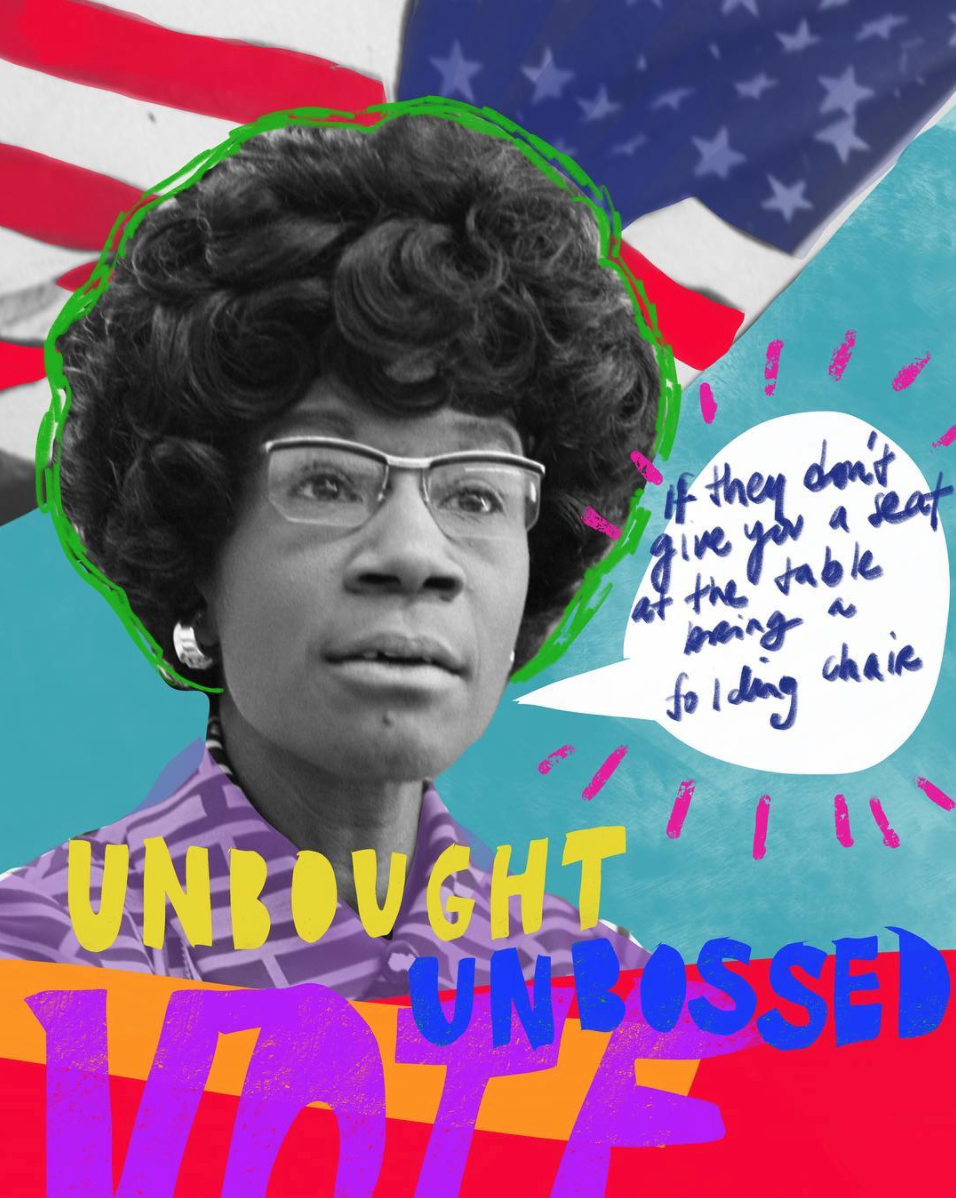

Aaron Marin

Unbought, Unbossed… Vote, 2018

Aaron Marin

Untitled (Fred Hampton), date unknown

V: Tell me more about the gallery idea.

A: The gallery is there to showcase work, have opening night parties, and garner attention to the artists to make them money—a meeting of people who love art, those who want to be seen, and everything in between. [Galleries] can be pretentious. The goal of mine is for it to just be a chill space; I want it to be a concierge into Black art and thought for Tokyo, or maybe an embassy. It’s a cultural attaché space for those seeking common ground. I don’t want to sound too “pie in the sky,” but I am a romantic.

V: How has your work been a place of respite for you as a creative human being amid this chaotic uncertainty of the current pandemic?

A: I don’t do as much work as I used to. I think more about what I’m feeling before I make a piece. Sometimes I cook, work out, or go for a drive to just be alone with my thoughts. The work is less respite and more catharsis—it’s purely my ideas filtered through the medium of collage. A lot of the thoughts I put in my artwork are subconscious, and it’s only when I’m removed from them through time and distance that I see what I was fully thinking and feeling. I’m planning a return trip to Japan this fall. * fingers crossed * That may or may not happen because of “The ‘Rona.” And because I’m increasingly reliant on digital means to create work, I have to update my aging (and dying) computers. So, saving money to afford expensive iPads and laptops is also something I’m doing. Art is expensive, and I have immense appreciation and respect for artists who make their livelihoods solely off of their work. It’s another goal of mine that I hope to be closer to [achieving] by the end of this year.

[This interview has been edited for style and clarity.]

Where to purchase

e hello.neutokyo@gmail.com

Instagram @neutokyo, @noraa_sketchbook

Support AMARIN40